Secondary CAD resolves after successful cancer treatment: Study

CT scan showed 59-year-old man had B-cell lymphoma, a type of blood cancer

Written by |

A case of cold agglutinin disease (CAD), found to be secondary to a type of blood cancer called B-cell lymphoma, successfully resolved after the cancer was appropriately treated, a study shows.

The case report illustrates the importance of identifying the underlying cause of CAD so treatment can be given, the researchers said in “Low-grade B cell lymphoma in the perirenal space of the left kidney associated with high titer cold agglutinin disease,” which was published in the American Journal of Blood Research.

A feature of CAD is the abnormal production of self-reactive antibodies called cold agglutinins that cause red blood cells to agglutinate (stick together) at cold temperatures, which marks them for destruction.

This can lead to anemia, or low numbers of red blood cells to carry oxygen around the body, along with fatigue, shortness of breath, and pale skin.

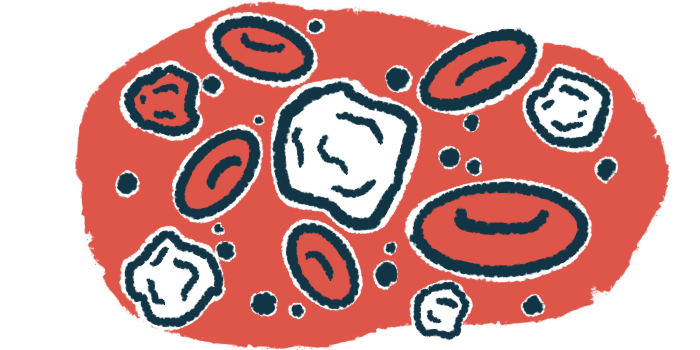

CAD is classified into two types, primary and secondary. Primary CAD is caused by the abnormal growth of cold agglutinin-producing B-cells in the bone marrow. Secondary CAD develops with blood cancers or infections.

B-cells are immune cells that produce antibodies, those that fight infections and cancer and self-reactive antibodies that drive autoimmune diseases such as CAD.

Looking for underlying cause of secondary CAD

Scientists at Uji-Tokushukai Medical Center, Japan described the case of a 59-year-old man who had CAD secondary to a slowly growing B-cell lymphoma in the tissue surrounding his left kidney. B-cell lymphoma is a type of blood cancer marked by the excess growth of B-cells.

The man had atrial fibrillation, a heart condition that causes the heart to beat irregularly or abnormally fast. While undergoing surgery for it, a blood test showed Rouleaux formation — red blood cells stuck together like stacks of coins. Further tests revealed very high levels of cold agglutinins.

The findings confirmed a diagnosis of CAD, but it wasn’t clear how long the man had been living with the disease without knowing it. He told clinicians he’d had some cold-related symptoms for at least six months.

Additional blood work showed normal hemoglobin levels, but higher than normal levels of markers of red blood cell destruction, or hemolysis, indicating the absence of significant hemolysis. He also had higher than normal levels of IgM, the most common type of antibody in cold agglutinins.

No signs of self-reactive antibodies associated with other autoimmune diseases nor signs of viral infections often linked to secondary CAD were seen.

Based on his mild hemolysis, “he was put on nonpharmacological management with thermal protection alone,” the researchers wrote.

Tests on his bone marrow were inconsistent with primary CAD, so clinicians looked for the underlying cause of the CAD through a series of tests.

Three months later, a CT scan of his abdomen revealed an unusual mass next to his left kidney. A biopsy determined it was a slowly growing B-cell lymphoma, leading to a diagnosis of secondary CAD due to lymphoma. Only 3-10% of lymphomas develop in that region around the kidneys.

The man was started on bendamustine, a chemotherapy used for lymphoma, and rituximab, which can deplete B-cells. The man’s cold agglutinin levels dropped dramatically after six cycles of treatment.

At the latest follow-up, nearly three years after the lymphoma was identified, the man’s cancer remains in remission and he hasn’t had any CAD symptoms.

“Whenever physicians are presented with a patient with chronic CAD and high cold agglutinin [levels], they should search for cause(s) such as lymphoma within/outside the bone marrow,” the scientists wrote. “If cases of lymphoma-associated CAS are appropriately treated with chemotherapy, symptoms/signs of CAD disappear and cold agglutinin [levels] decline rapidly.”