Targeting Complement Pathway May Offer New Therapies for CAD

Written by |

New therapies that target the complement pathway — a type of immune response that involves the production of antibodies — could help improve the treatment of cold agglutinin disease and other hemolytic anemias, a review study says. Clinical trials testing such therapies are recruiting patients.

The article, “Complement Activation and Inhibition in Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia: Focus on Cold Agglutinin Disease,” was published in Seminar in Hematology.

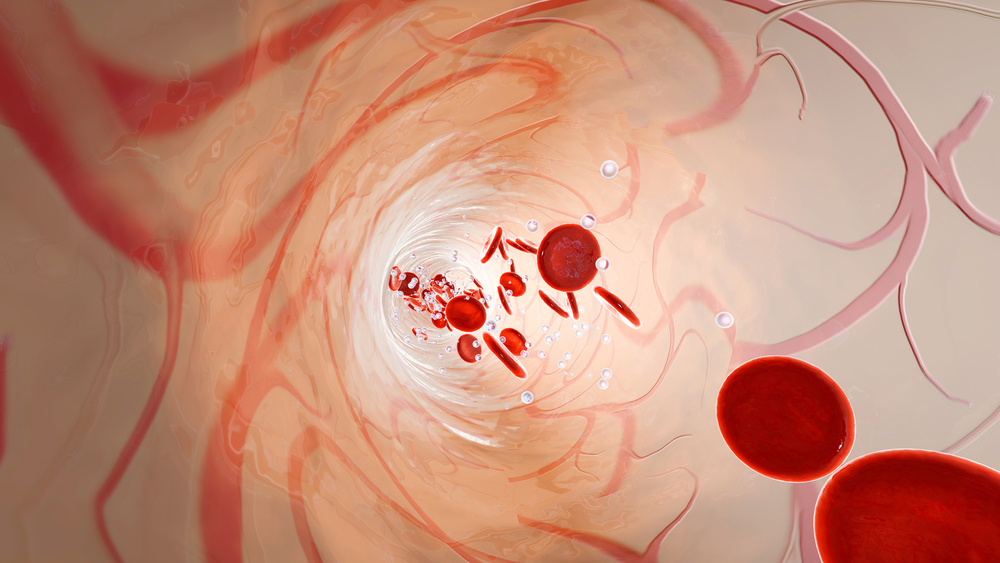

Cold agglutinin disease (CAD) is a kind of hemolytic anemia, a group of autoimmune diseases where the immune system attacks and destroys the body’s red blood cells.

Hemolytic anemia is triggered by autoantibodies (antibodies that recognize the body’s own tissues as harmful) that bind to the red blood cells, causing them to form aggregates that are later destroyed.

CAD accounts for 15-25% of cases of hemolytic anemia and mainly affects middle-aged and older people. The autoantibodies in CAD patients bind the red blood cells at low temperatures (3-4ºC/37-39ºF), so the autoimmune response primarily occurs in the limbs. Symptoms get worse in cold weather.

Bacterial infections also trigger CAD symptoms because molecules of the complement pathway increase as a response to external pathogens.

People with mild cases of the disease do not need to take medication. They should avoid exposure to the cold, wear warm clothes, avoid drinking cold beverages, and treat bacterial infections as soon as possible.

However, 70-80% of patients need medication to treat the symptoms. Patients often must take several medications because the effects only last for a short period.

Rituxan (rituximab), which targets B-cells — the cells that produce antibodies — is a safe treatment for CAD and has an estimated response rate of 50%. However, almost all remissions are only partial and the time of response duration is a median of 11 months. This treatment is often used in combination with other immunosuppressants.

Therapies that target components of the complement pathway are being developed. The first available for clinical use was a plasma-derived C1-esterase inhibitor (C1-INH). C1 is a member of the complement pathway.

The treatment was approved for hereditary angioedema but has been used off-label in complement pathway-dependent diseases. It has shown good results, but high doses are required.

Soliris (eculizumab), distributed by Alexion, targets the complement molecule C5. It decreased hemolysis (red blood cell destruction) and reduced the necessity of transfusion in a prospective clinical trial evaluating 13 patients.

Another potential candidate, BIVV009 (Sutimlimab, Sanofi), which inhibits the complement component C1, showed positive results in a Phase 1 trial and is being evaluated in two Phase 3 clinical trials (NCT03347396 and NCT03347422). The latter is still recruiting.

APL-2 (Apellis Pharmaceuticals) showed positive results in two Phase 1 clinical trials and is being tested in a Phase 2 clinical trial (NCT03226678).

“In contrast to B-cell directed therapies for CAD, which are completed after administration of a few cycles, complement-directed therapies will probably have to be continued [indefinitely] to maintain their effect. Probably, most complement inhibitors will also be very expensive,” the authors noted.

Nevertheless, therapies that target the complement may show a more rapid response than those targeting B-cells.

“CAD patients who have profound hemolytic anemia and those with severe exacerbations may profit from this short [time to response], which will offer a bridge to the more slowly acting B-cell directed therapies. Furthermore, complement inhibition may become useful as prophylaxis during cardiac or other major surgery,” they concluded.