Sutimlimab Safe, Effective as Long-term Therapy for CAD, Study Finds

Written by |

Long-term maintenance treatment with sutimlimab is safe, prevents red blood cell destruction, and increases the amount of hemoglobin in people with cold agglutinin disease (CAD), avoiding the need for blood transfusions.

Those findings are detailed in the study “Inhibition of complement C1s in patients with cold agglutinin disease: lessons learned from a named patient program,” which was published in the journal Blood Advances.

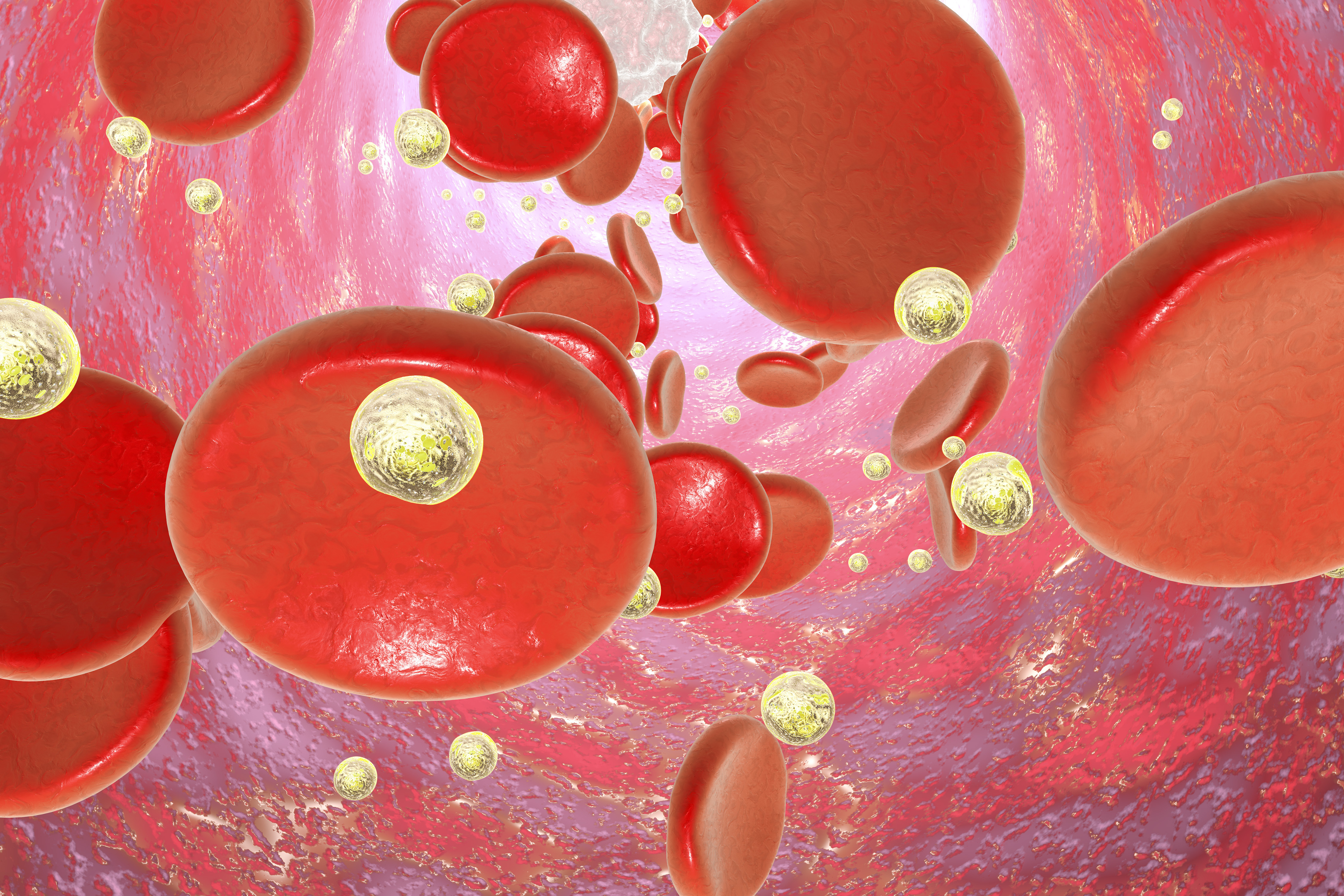

CAD is a rare autoimmune disorder in which exposure to cold temperatures causes autoantibodies (antibodies directed against the body’s own tissues) to bind tightly to red blood cells, causing their disintegration and leading to anemia.

This disease is mostly mediated by the complement system, a set of more than 30 proteins normally involved in innate (natural) immune responses.

Sanofi‘s sutimlimab is an antibody designed to block the C1 complement protein, stopping the classical complement signaling cascade in its earlier stages, before it results in hemolytic anemia (anemia caused by rupture of red blood cells).

The treatment is showing promise in multiple clinical trials for CAD patients, including the CARDINAL Phase 3 trial (NCT03347396), in which sutimlimab increased the amount of hemoglobin (a key component of red blood cells), improved quality of life, and avoided the need for blood transfusions in most CAD patients.

To find out whether sutimlimab’s effects can be maintained in the long run, researchers in Austria and in the U.K. conducted a named patient program with seven of the 10 CAD patients included in a Phase 1b trial of sutimlimab (NCT02502903).

Participants in this subset of the trial had received four weekly doses of sutimlimab, which effectively inhibited red blood cell disruption, increased the amount of hemoglobin in the blood, and prevented blood transfusions in all those who were dependent on the procedure.

In the Sanofi-funded program, sutimlimab was given via intravenous (into-the-vein) infusions every two weeks. The starting dose was 45 mg/kg for three patients, 60 mg/kg for another three participants, and one patient received a fixed-dose of 5.5 g. Signs of hemolysis prompted dose increases.

Sutimlimab treatment, which lasted from two to 20 months, rapidly increased hemoglobin to levels close to normal in all patients, reaching a median peak of 12.5 g/dL that was maintained throughout the study. (Normal hemoglobin levels in women range from 12 to 15.5 g/dL and in men from 13.5 to 17.5 g/dL)

Treatment also lowered bilirubin levels, reduced the amount of lactate dehydrogenase, and increased median levels of haptoglobin (which binds to hemoglobin), all of which suggested less red blood cell destruction and complement activation.

In some cases, patients experienced signs of hemolysis, which researchers attribute to insufficient dosing levels to maintain treatment effects for 14 days. After increasing doses, hemoglobin levels rapidly increased in most cases.

Both the CARDINAL trial and a Phase 2 study (NCT03347422) are exploring higher and more frequent sutimlimab doses to avoid the risk of hemolysis due to insufficient doses.

Adverse side effects were mostly mild-to-moderate, and usually were gastrointestinal problems (10%), palpitations (6%), common cold (6%), sore throat (6%), and night sweats (5%). Overall, sutimlimab infusions were well-tolerated, with only one adverse side effect deemed related to treatment.

Also, the treatment was safe when used in combination with other therapies (such as rituximab), without increasing the susceptibility to infections.

“The [named patient program] showed that biweekly infusion therapy with sutimlimab was safe, effectively abrogated complement-mediated hemolysis, and increased and maintained hemoglobin at near normal levels in all patients upon re-exposure,” the researchers wrote.

“[C1 protein] inhibition by sutimlimab seems to be an effective therapeutic strategy for long-term treatment of CAD patients,” they added.