Subtle CAD Symptoms in Patients Often Missed: ‘Incidental’ Case Study

Written by |

The symptoms of cold agglutinin disease (CAD) often can be overlooked due to their subtlety — particularly in patients with co-existing conditions — a recently reported case of incidental CAD highlights.

In the report, researchers in India described a man with a complicated medical history who was admitted on a cold winter morning to the emergency room for alcohol withdrawal syndrome. He was subsequently, and incidentally, diagnosed with CAD.

Notably, the man was only diagnosed with CAD after a series of blood tests.

“Recognition of CAD is important as [symptoms] may be subtle in clinical presentation and may be missed initially if overlooked while interpreting [other patient information],” the researchers wrote.

The study, “Coomb’s negative cold agglutinin disease: A rare report of an incidentally detected case,” was published in the Asian Journal of Transfusion Science.

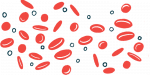

CAD is an autoimmune disorder in which self-reactive antibodies — antibodies that react against a person’s own tissues or cells — attack and destroy red blood cells at cold temperatures.

These red blood cells then agglutinate, or clump together, and ultimately die, resulting in anemia, fatigue, and pain.

However, many other diseases also cause pain and fatigue, and can lead to decreased oxygenation, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Such co-existing conditions, called comorbidities, may complicate a CAD diagnosis.

Here, researchers reported the case of a 54-year-old man who was delirious and brought to the hospital’s emergency room on a cold morning in winter. The patient had a history of COPD and alcoholism. He was admitted with a case of alcohol withdrawal syndrome — with symptoms, which can be life-threatening, that occur when someone stops drinking alcohol after a period of heavy drinking.

A day after his admission, his condition deteriorated. The patient developed high fever with cough, decreased blood pressure, and low blood oxygen levels. Further tests showed he had severe respiratory acidosis — a condition in which the lungs cannot efficiently remove carbon dioxide from the bloodstream.

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit with sepsis and respiratory distress.

Blood tests revealed he had anemia, with hemoglobin levels at 9.2 grams per deciliter (g/dL). Hemoglobin is the protein in red blood cells that is responsible for oxygen transport. Normal hemoglobin levels for men usually range between 13.5–17.5 g/dL.

Additionally, his red blood cell count was low, with 1.6 million cells per cubic millimeter (million/mm3). Normal red blood cell numbers range between 3.93–5.69 million/mm3.

“Falsely low [red blood cell] count can be explained by the fact that [red blood cell] agglutinates become so large in size that analyzers either identify as a single white blood cell (WBC) or single [red blood cell] or they are totally excluded from the count,” the researchers wrote regarding low blood cell counts in CAD.

Furthermore, the patient’s mean corpuscular volume (MCV) — the average size and volume of red blood cells in a sample — was 106 femtoliters (fL), as compared with the normal range of 80–100 fL.

Meanwhile, the average amount of hemoglobin in each blood cell, a measure called the mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC), was high. Specifically, the patient’s MCHC was 55.2 g/dL, as compared with the normal range of 33.4–35.5 g/dL. According to the authors, these two parameters were increased due to red blood cell agglutination.

A blood smear, which looks at the shape of blood cells, showed that there were clumps of red blood cells throughout the patient’s blood sample.

Also, the patient’s serum sample — the liquid part of the blood — was slightly pink, indicative of hemoglobinemia. Hemoglobinemia, or free hemoglobin in the serum, often occurs due to red blood cell destruction.

The clinicians noticed the patient’s blood showed signs of agglutination even to the naked eye within its collection tube. This clumping disappeared at body temperature, 37 C (98.6 F), and returned upon refrigeration. Red blood cell agglutination was confirmed under a microscope.

Agglutination also occurred when the patients’ red blood cells — washed of any other cells or serum proteins — were allowed to react with his serum at cold temperatures, of 4C (39.2 F).

However, a Coomb’s test, which is used to detect antibodies bound to red blood cells, such as those associated with CAD, was negative. This was a surprising finding, as noted by researchers.

They suggested different possible reasons for this negative test result, including technical errors in performing the test or an instance in which the destroyed red blood cells, which are the most coated in self-reactive antibodies, are quickly cleared from the blood.

Ultimately, based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with incidental CAD, along with alcohol withdrawal syndrome and atypical pneumonia based on X-ray scans. He was treated for his illnesses and discharged with a recommendation to avoid exposure to cold temperatures.

The researchers noted that the CAD diagnosis was incidental to the patient’s other comorbidities, but important for preventing future attacks.

“The importance of diagnosing CAD lies in the fact that the patient needs to be explained carefully for prevention of attacks in the future by counseling the individual to wear appropriate clothing and avoiding cold exposure,” they wrote.