CAD Least Common Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia in India, Study Suggests

Written by |

Cold agglutinin disease (CAD) seems to be the least common form of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) in India, affecting about 15% of patients with the rare disorder, a study has found.

The study, “Immunohematological work‐up, severity analysis and transfusion support in autoimmune hemolytic anemia patients,” was published in the journal ISBT Science Series.

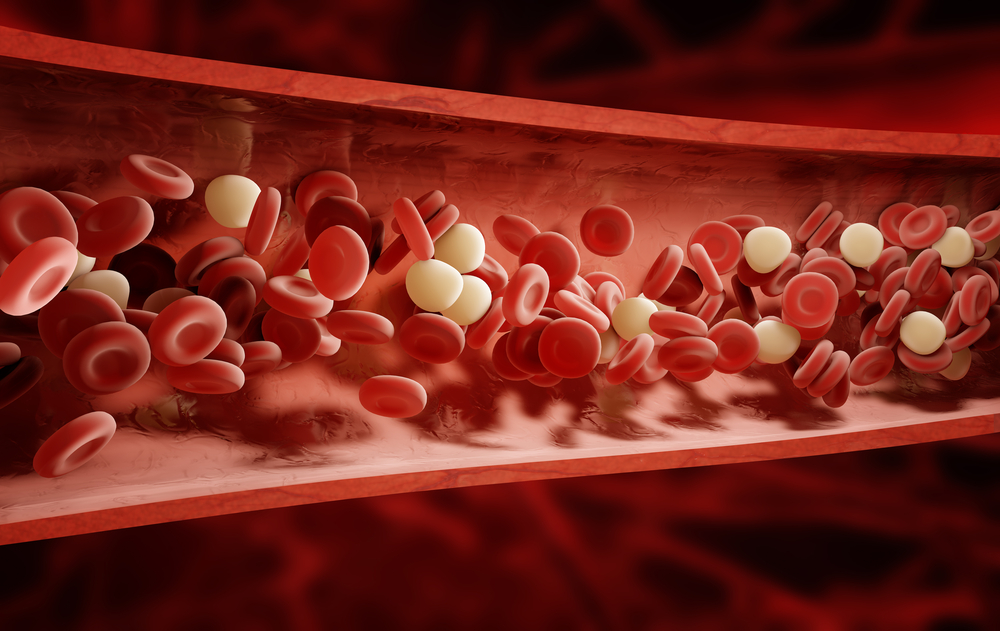

AIHA is an autoimmune disease in which autoantibodies attack and destroy red blood cells. It has three subtypes, based on the temperature at which the antibodies — called autoagglutinins — bind to red blood cells. These are warm, cold, and mixed – which, as the name implies, has a mixture of antibodies working at cold and warm temperatures.

Binding of these antibodies causes red blood cell clumping, which triggers an immune reaction leading to hemolysis, or the rupture of red blood cells. The resulting loss of these cells causes anemia.

In India, the prevalence and severity of AIHA, as well as patient transfusion needs, are not well documented. This prompted researchers at the Sriram Chandra Bhanja Medical College and Hospital in Cuttack, India, to look for AIHA among anemic patients and document their findings.

They identified 94 cases at the hospital from September 2015 to September 2017, with patients ranging in age from 2 to 74.

Warm AIHA was the most common subtype, comprising 58 patients, or 61.4% of the group. Mixed AIHA and CAD followed in frequency, with 22 patients (23.7%) and 14 patients (15%), respectively.

Overall, females were more affected than males, making up 67% of warm-type cases, 77% of mixed, and 58% of CAD cases.

Most of these cases, or 56%, occurred following other autoimmune disorders, infection, or cancer. In these instances, the disorder is known as secondary AIHA. Primary AIHA, which occurs without a known underlying cause, accounted for the remaining 44%.

Hemolysis was classified as moderate (39.6%) or severe (60.4%). The severity of hemolysis only correlated significantly with the direct antiglobulin test (DAT) — a measure of whether, and to what extent, red blood cells are covered with antibodies.

The researchers found no significant correlations between the severity of hemolysis and gender, type of AIHA, or type of antibody. Nonetheless, some antibody differences were observed among AIHA types.

While 67% of patients with both IgG and C3d antibodies — antibodies that cause the lysis of red blood cells — had severe hemolysis, this occurred in 58% of those in whom only IgG or C3d was detected. The investigators suggest that multiple antibodies may act to cause severe hemolysis.

Overall, 38 patients with severe anemia needed blood transfusions. These included 34% of those with warm AIHA, 43% of CAD patients, and 55% of patients with the mixed subtype.

Secondary AIHA cases needed more transfusions than primary cases (56.6% vs. 19.5%).

A total of 14 transfusion cases (seven warm, five mixed, and two cold) lacked compatible blood units. Based on evidence suggesting that patients urgently needing transfusion benefit more from incompatible blood than from none, these patients received antigen-negative best-match blood units.

“Though best-matched blood units were transfused to these patients, the survival of these red cells needs to be studied,” the investigators wrote.

Although larger studies are needed and patient responses to medications should be evaluated, the results of the current study may inform future treatment decisions.

“It is necessary to diagnose the type of AIHA and type of antibody, that is, IgG or C3d present on the RBC surface as the modality of treatment and the approach to transfusion support changes as per the type of AIHA,” they concluded.