B-cell clones found to be driver of woman’s CAD: Case study

Out-of-control cell growth sparks disease in 78-year-old

Written by |

An underlying disorder involving abnormal cell growth turned out to be at the root of cold agglutinin disease (CAD) in a 78-year-old woman.

The woman had monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL), a condition that occurs when a group of identical white blood cells, in this case B-cells, grows abnormally, a case study reported.

The researchers said that recognizing abnormal B-cell growth and following special laboratory procedures — such as keeping blood samples warm during testing — are important steps in accurately diagnosing CAD.

The case report, “Cold agglutinin disease with associated monoclonal B cell lymphocytosis: It takes two to tango!” was published in Medical Journal Armed Forces India.

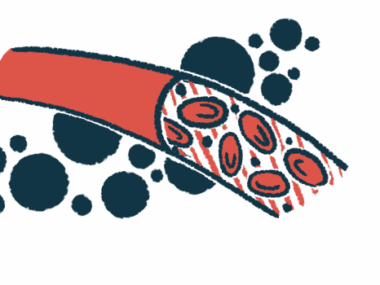

CAD occurs when the body’s immune system makes antibodies that mistakenly attack its own red blood cells. These antibodies, called cold agglutinins, become active at cooler temperatures. When activated, the antibodies cause red blood cells to stick together and trigger other parts of the immune system to break them down. This destruction leads to anemia, a shortage of red blood cells. Since red blood cells carry oxygen throughout the body, anemia reduces oxygen delivery and can cause CAD symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, pale skin, and circulation problems or yellowing of the skin (jaundice).

“It can be difficult for hematologists and pathologists to accurately diagnose CAD,” the researchers wrote. CAD diagnosis usually requires assessing symptoms and laboratory test results, as well as excluding other possible conditions. Understanding the underlying causes of CAD might help with diagnosis and treatment.

An unusual connection

CAD is recognized as a disorder driven by the clonal growth of abnormal B-cells (lymphoproliferation) in the bone marrow that produce cold agglutinins. Because these clonal cells keep making the same self-reactive antibody, they fuel ongoing disease activity.

Treatments like rituximab (sold as Rituxan and biosimilars), commonly used in blood cancers, can help in CAD by targeting and reducing these abnormal B-cells, lowering cold agglutinin production.

The researchers identified an unusual connection between CAD and MBL, a condition in which a small population of identical B-cells circulates in the blood. While MBL is often harmless, in this case, the clonal B-cells were responsible for producing cold agglutinins and driving CAD.

The woman described in the case report had experienced two months of worsening fatigue and jaundice, with routine blood tests repeatedly registering clotted samples. On closer inspection, the issue was found to be not clots but red blood cells sticking together — a reaction caused by abnormal antibodies. When the samples were kept warm, at a temperature of 37º C (about 98.6º F), the machines could process them normally, revealing clear signs of anemia and ongoing breakdown of red blood cells.

Further testing showed that the woman’s immune system was producing cold agglutinins as well as a small population of identical B-cells. Because these cells were all clones of each other, the condition was classified as MBL. The abnormal B-cells were the source of the harmful antibodies that caused her CAD.

“An elderly woman patient with anemia who frequently has clotted samples should alert clinicians to further workup for CAD by her clinical history and typical cold-induced symptoms,” the researchers wrote.

After ruling out infections or other causes, the clinical team treated the woman with a combination of rituximab and bendamustine, a chemotherapy drug that can help address B-cell growth. She responded well to treatment, and follow-up blood samples showed that her red blood cells no longer clumped together.

Due to the difficulty in correctly diagnosing CAD, “it is crucial to identify the [disease-causing] characteristics of the lymphoproliferative condition linked to cold agglutinin disease,” the researchers concluded.